Psychosis & Schizophrenia

Seminar for Lyra Health · June 2025

PD Dr. med. Veith Weilnhammer

Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute & Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Research Center

University of California Berkeley

What comes to mind when you hear the word psychosis?

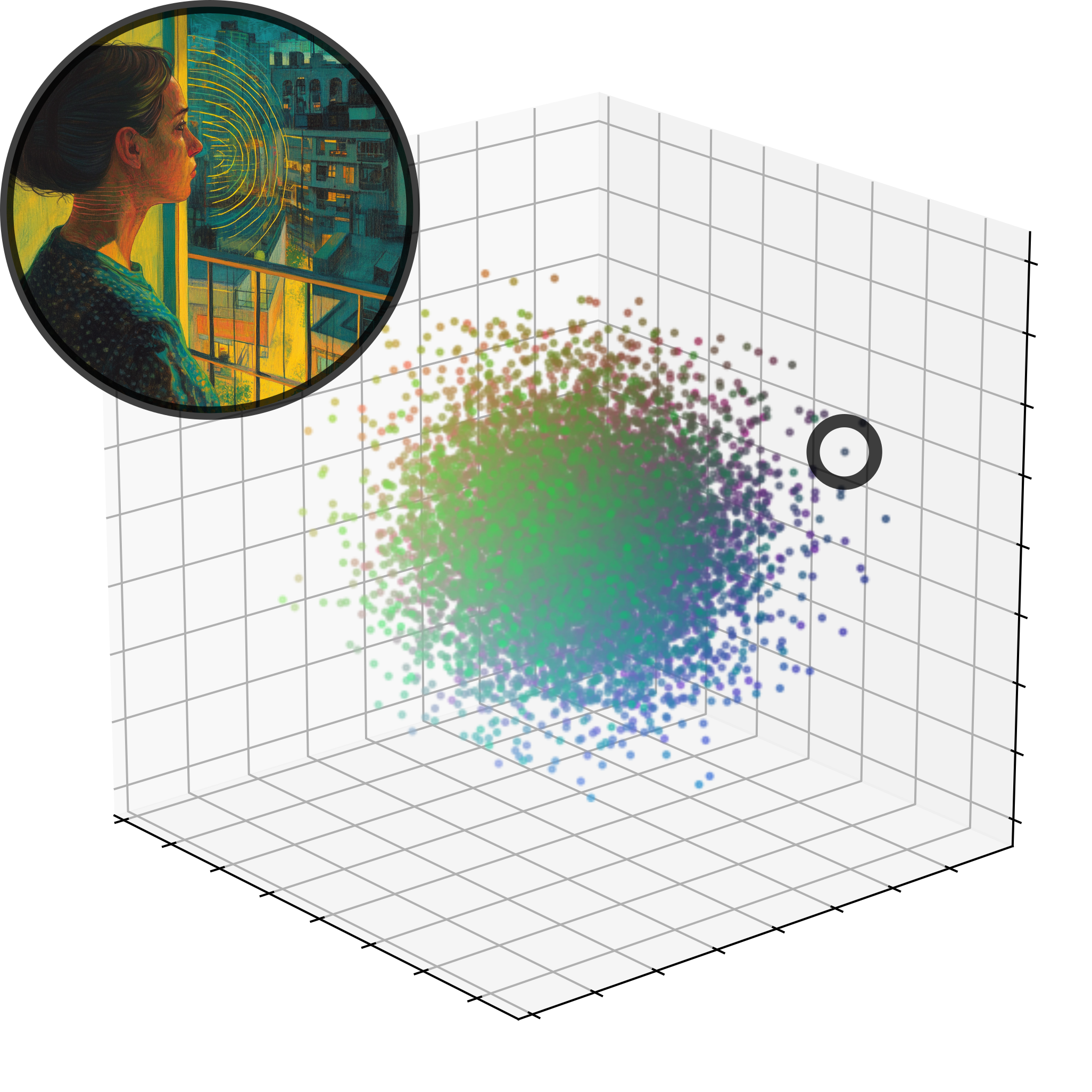

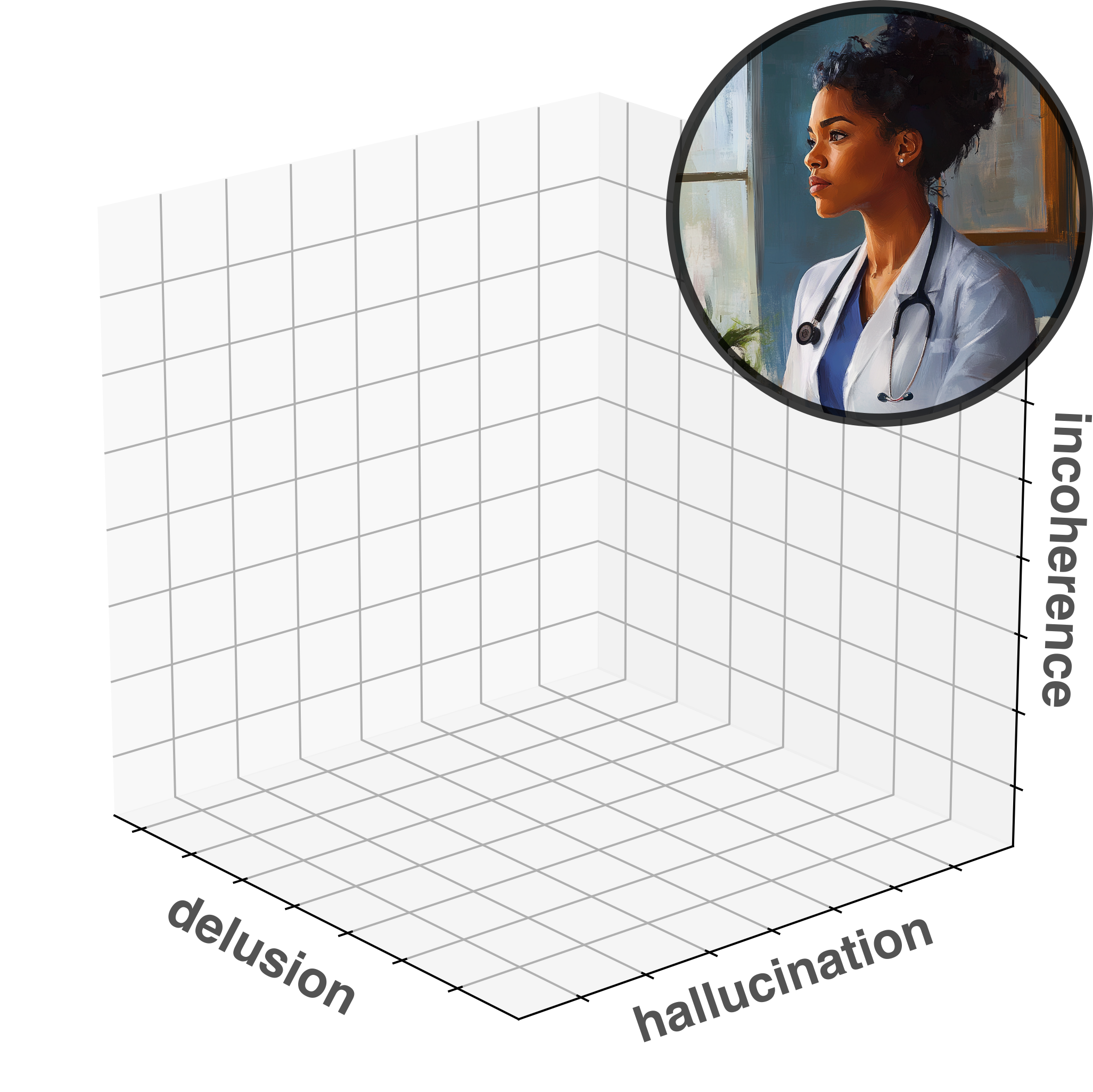

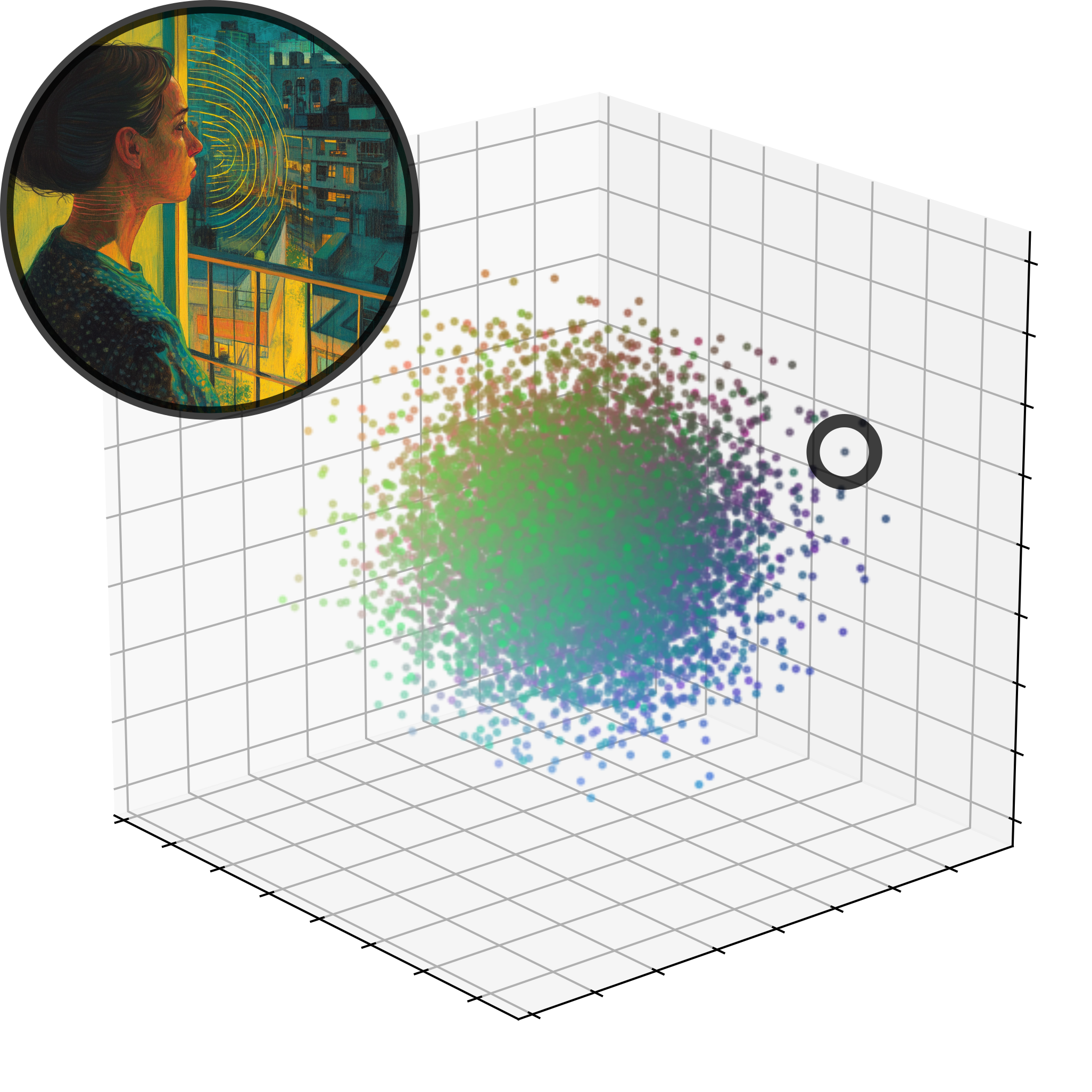

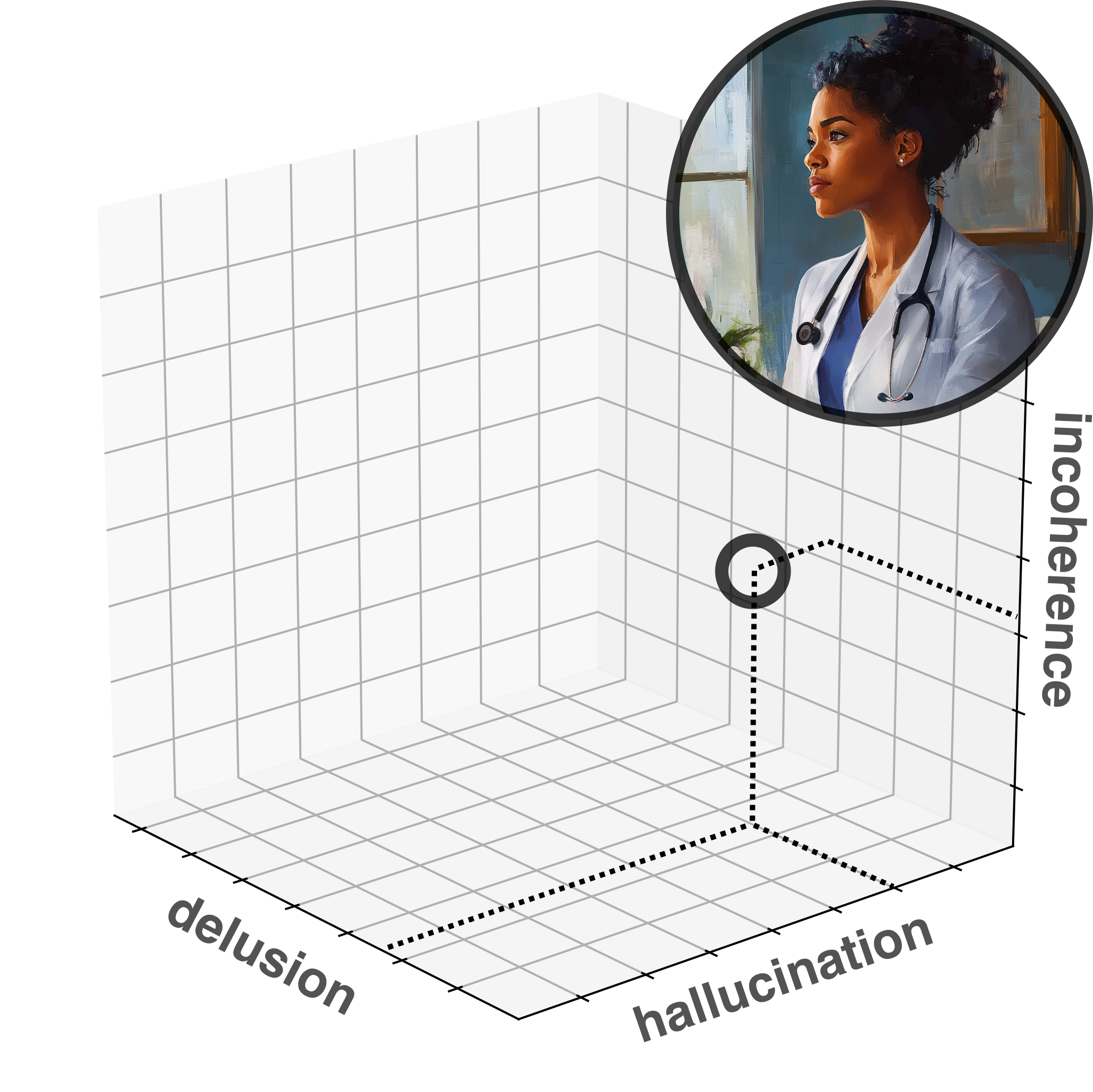

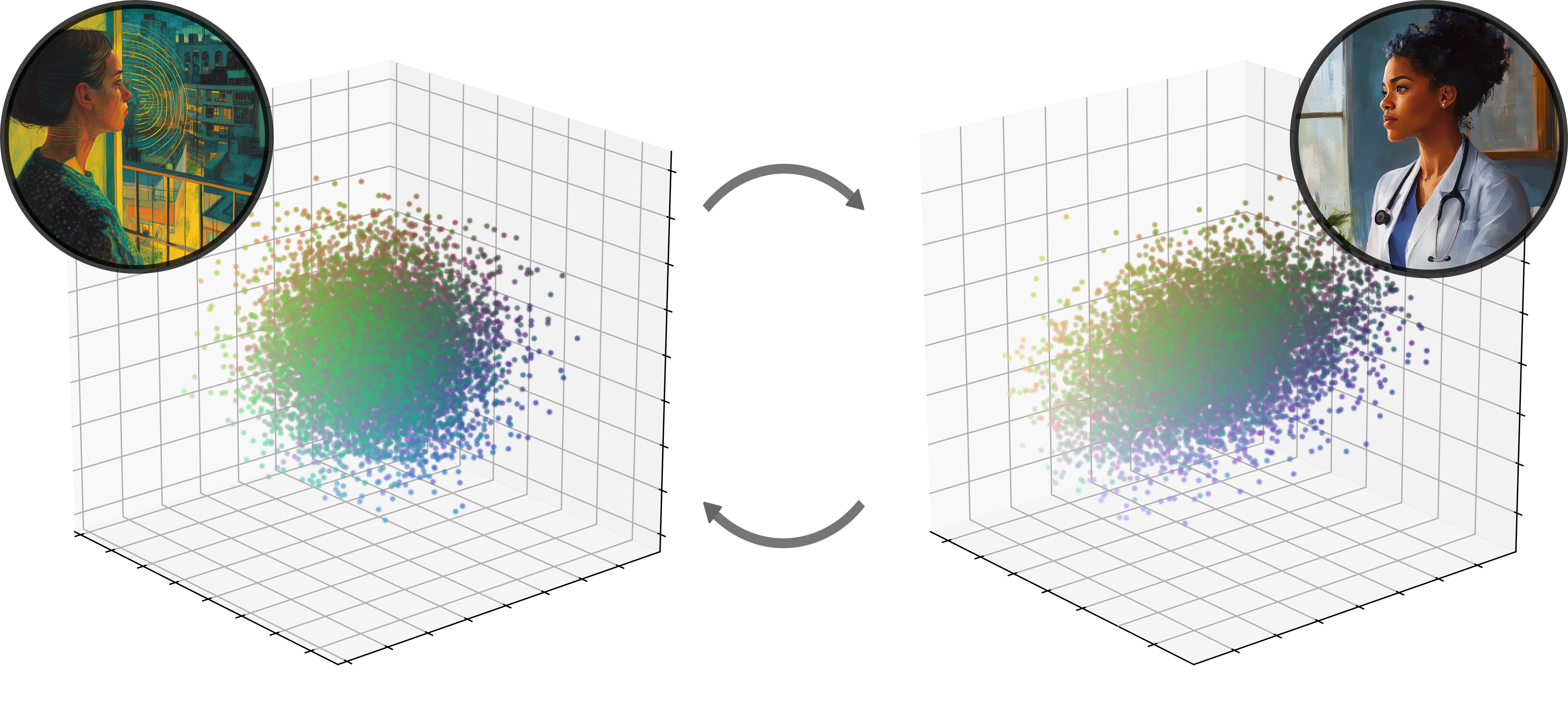

The geometry of mental health

Mrs. X

Mrs. X

It started with strange noises through the wall, quiet and barely recognizable, as if someone were eavesdropping.

Over time, I could make out the voice of my neighbor. I had to investigate.

At first, I only heard his voice in my apartment, but later he followed me to other places.

Then it dawned on me - he's an agent!

Dr. Y

Clinical representations

Clinical representations

Diagnosis

Heterogeneity

Lost in translation

Found in translation

Mission of Lyra Health: To make high-quality mental health care available to all.

Agenda

An overview on psychosis

Real-world Case studies and reflections

Agenda

An overview on psychosis

What are psychotic experiences?

Epidemiology & course

Causes & risk factors

Assessment & flags

Communication strategies

Evidenced-based treatment

Real-world Case studies and reflections

Agenda

An overview on psychosis

Real-world Case studies and reflections

The Suspicious Neighbor: Emerging paranoia and early intervention

Voices on the Line: Acute psychosis during a crisis call

The Impostor Family: Delusional misidentification and trauma

The Silent Withdrawal: Subtle onset in a high-functioning individual

What are you most curious about?

An overview on psychosis

What are psychotic experiences?

It started with strange noises through the wall, quiet and barely recognizable, as if someone were eavesdropping.

Over time, I could make out the voice of my neighbor. I had to investigate.

At first, I only heard his voice in my apartment, but later he followed me to other places.

Then it dawned on me - he's an agent!

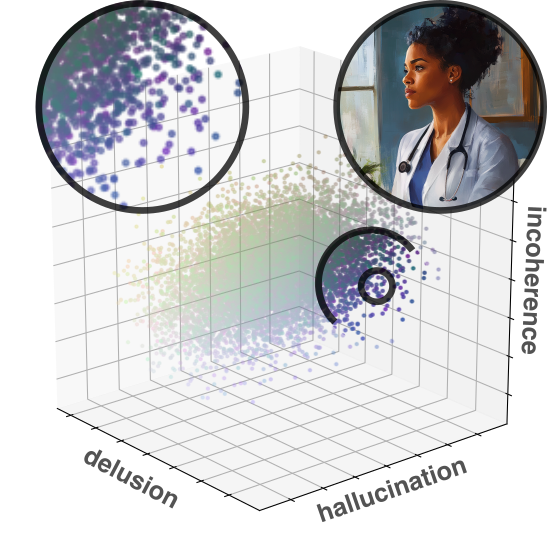

General Definition

Psychotic experiences refer to disruptions in the way a person perceives, interprets, or connects with reality.

They include alterations in perception (e.g. hearing voices), thought content (e.g. delusions), speech, and behavior.

They reflect a breakdown of reality monitoring—the ability to distinguish internal experiences from external events.

Common Phenomena

Hallucinations: Perceptual experiences without external stimuli (e.g. voices, visions)

Delusions: Fixed, false beliefs (e.g. paranoia, grandiosity)

Disorganized Speech: Tangential, incoherent, or illogical language

Thought Insertion: Belief that thoughts are being placed in one's mind

Passivity Experiences: Feeling controlled by external forces

Psychotic disorders

Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

Brief Psychotic Disorder

Schizoaffective Disorder

Bipolar Disorder (with psychotic features)

Major Depression (with psychotic features)

Delusional Disorder

Substance- or Medication-Induced Psychotic Disorder

DSM-5 Criteria for Schizophrenia

Criterion A – Core Symptoms:

- Two or more of the following, present for ≥1 month. At least one must be (1), (2), or (3):

- (1-3) Delusions, Hallucinations, Disorganized speech

- (4-5) Disorganized/catatonic behavior, negative symptoms

Criterion B – Functional Impairment: Work, relationships, or self-care markedly below prior functioning

Criterion C – Duration: Continuous signs of disturbance for ≥6 months, including ≥1 month of active symptoms

Criterion D – Mood Exclusion: Schizoaffective disorder and mood disorders with psychotic features must be ruled out

Criterion E – Substance/Medical Exclusion

Criterion F – Neurodevelopmental Exclusion: In ASD or communication disorders, schizophrenia is diagnosed only if delusions or hallucinations are prominent and persist for ≥1 month

Specifiers: Include course (e.g. first episode, remission), severity, and catatonia

ICD-10 vs ICD-11 Criteria for Schizophrenia

Core Symptoms:

- Both require ≥1 first-rank or equivalent symptoms (e.g., thought insertion, delusional perception)

Duration: Psychotic symptoms must persist for ≥1 month in both systems

Functionality:

- ICD-10: Does not require functional impairment

- ICD-11: Still does not require it, but impairment may support diagnosis

Subtypes:

- ICD-10 includes subtypes (e.g., paranoid, hebephrenic, catatonic)

- ICD-11 removes subtypes entirely

Symptom Specifiers: (ICD-11 only)

- Positive symptoms, Negative symptoms

- Depressive, Manic, Psychomotor, Cognitive

Course Specifiers:

- ICD-10: episodic/continuous/remission patterns

- ICD-11: structured specifiers (e.g., first episode in remission, multiple episodes in acute phase)

Psychosis (Syndrome)

- Definition: A state in which a person loses contact with reality.

- Can occur in:

- Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder, Depression etc.

- Substance use (e.g. stimulants, cannabis)

- Medical conditions (epilepsy, NMDAR encephalitis etc.)

- Symptoms:

- Hallucinations (most often auditory)

- Delusions (often paranoid or grandiose)

- Disorganized thoughts or behavior

- Agitation or confusion

- Duration: Can be brief or prolonged

- Course: May resolve fully or recur

Schizophrenia (Diagnosis)

- Definition: A chronic mental illness involving disruptions in thought, perception, and affect.

- Core Features:

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Disorganized speech

- Negative symptoms (e.g. flat affect, social withdrawal)

- Catatonic behavior

- Diagnostic Criteria (DSM-5):

- ≥2 core symptoms, one must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech

- Present for ≥1 month, with total illness duration ≥6 months

- Marked social or occupational dysfunction

- Course: Episodic or continuous; often lifelong support needed

Summary: What is Psychosis?

Altered connection to reality, across multiple diagnostic groups

Core features: hallucinations, delusions, disorganization, and loss of insight

DSM-5, ICD-10, and ICD-11 converge on symptom patterns, but differ in structure

Course and Epidemiology

How common are psychotic experiences?

When do they start?

What happens after diagnosis?

Early: It began slowly. I was 19. First, I couldn’t sleep. Then I felt like people on the bus were talking about me.

By 21, I had dropped out of university. I thought my professors were recording my thoughts.

They took me to the hospital after I stood outside in the rain all night, convinced the sky was trying to send me messages.

In treatment: After the hospital, things got quiet. Too quiet. My family said I was better, but I did not feel very much.

I started antipsychotics, moved back in with my mother, and stopped speaking much. I had trouble concentrating, and was sleepy most of the time. I lost my phone three times in a month!

Long-term course: Years have passed. I have some good days. I volunteer now and then. But the world still feels distant, like it’s behind glass.

Global & Demographic

Prevalence: Schizophrenia affects about 1 in 200 people globally (~0.5%).

Incidence is slightly higher in urban vs. rural areas, and among migrants and vulnerable populations.

Men are affected earlier (late teens to early 20s), women typically later (late 20s to early 30s).

Global & Demographic

Typical Trajectory

Prodromal Phase: Often includes social withdrawal, reduced motivation, subtle emotional or cognitive changes.

First Episode: Characterized by acute psychosis, usually requiring hospitalization.

Afterward: Symptom course varies: may remit, recur, or become chronic depending on factors like support, early intervention, and adherence.

Typical Trajectory

Heterogeneity and Hope

~ 20% of individuals recover fully with treatment and support

~ 40% experience intermittent relapses with significant periods of stability

~ 40% have chronic symptoms, often dominated by negative or cognitive deficits

Factors predicting better outcome: female sex, later onset, short duration of untreated psychosis, good premorbid functioning, and social support

Early intervention services significantly improve outcomes

Summary: Course & Epidemiology

Schizophrenia affects ~0.5% of the population — more than many chronic neurological illnesses

Typical onset is in late adolescence or early adulthood, earlier in men than women

Course varies: some recover fully, others experience relapses or chronic symptoms

Early signs include subtle cognitive and social changes (prodrome), followed by acute psychosis

Prognosis improves with early intervention, support, and treatment adherence

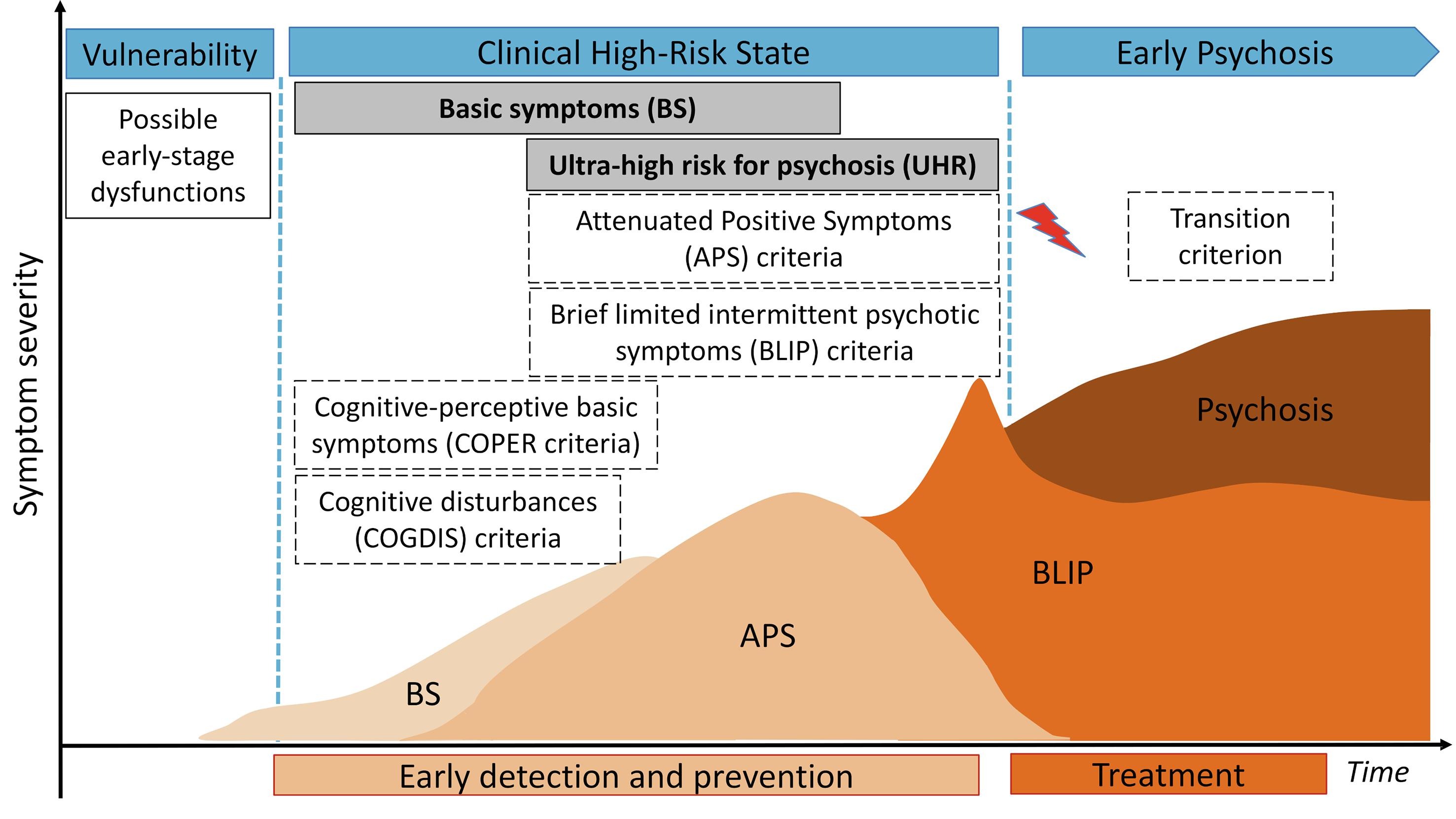

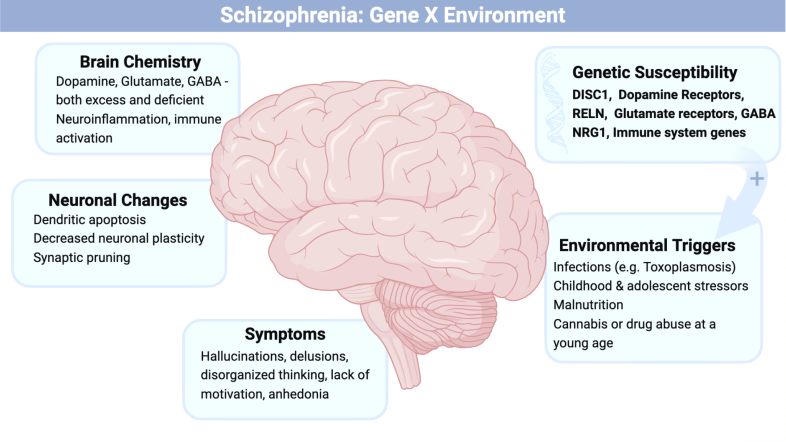

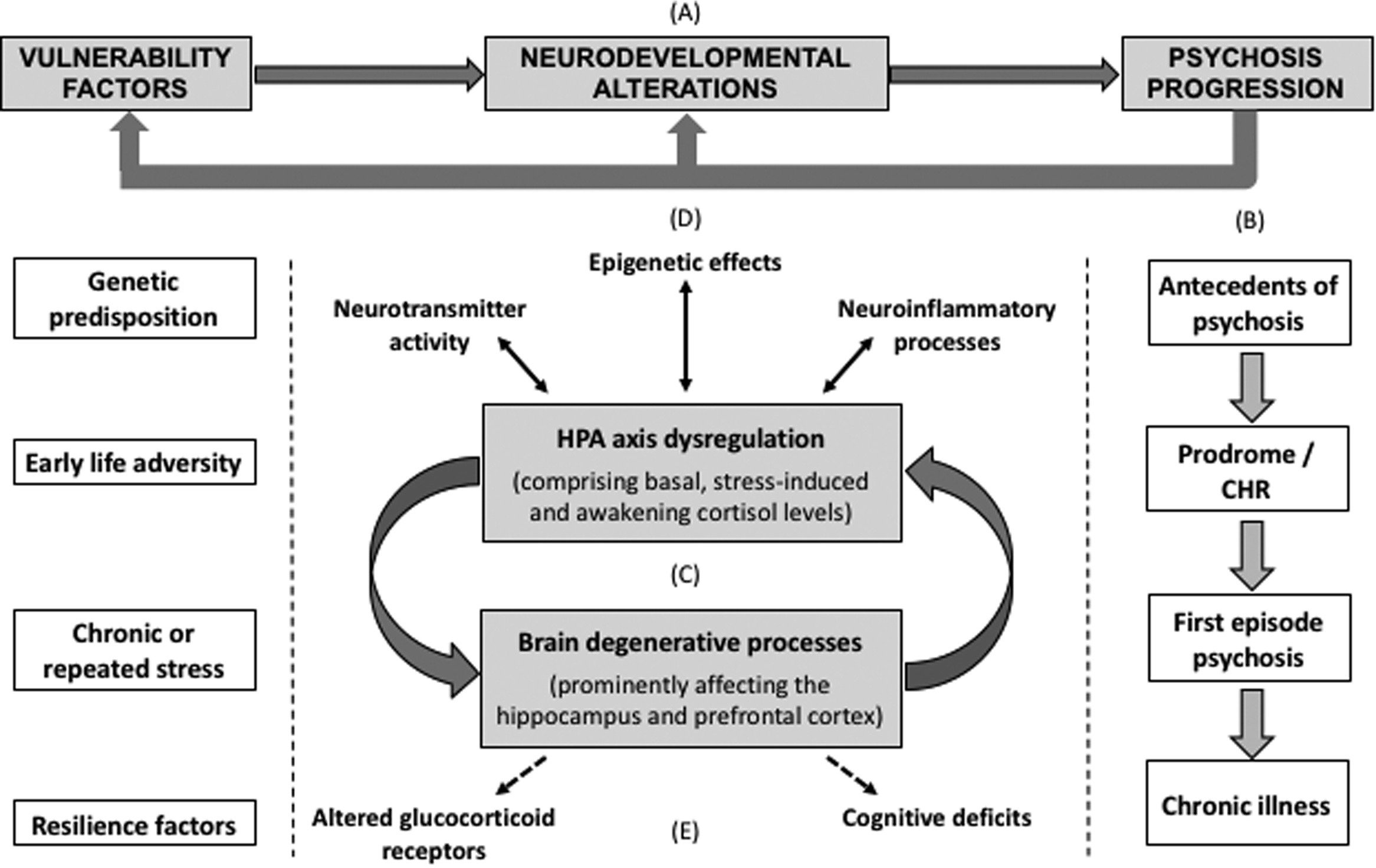

Causes & Risk Factors

What contributes to psychosis?

Mrs. X was always a sensitive child—quiet, withdrawn, lost in thought.

In adolescence, she struggled with anxiety and feelings of detachment.

After a stressful breakup and increased cannabis use, the voices began.

She later learned that her uncle had been hospitalized with similar symptoms.

Vulnerability & Triggers

Genetic predisposition: Family history increases risk

Early adversity: Trauma, neglect, or abuse during childhood

Substance use: Especially cannabis, amphetamines, psychedelics

Stress & life events: Breakups, migration, academic stress

Neurodevelopmental factors: Complications during birth or development

Vulnerability & Triggers

How causes interact

Diathesis-Stress Model: Psychosis emerges when vulnerability meets stress

Cognitive Model: Maladaptive interpretations of internal experiences

Neurodevelopmental Model: Early brain insults predispose to later symptoms

Biopsychosocial Integration: No single cause—multiple levels interact

How causes interact

Summary: Causes & Risks

Genetic risk, early trauma, and drug use can all increase the likelihood of psychosis.

Stress and misinterpretation of internal signals may act as triggers.

Modern theories emphasize interactions across biology, psychology, and context.

If you could reduce one societal risk factor for psychosis, what would it be?

Assessment & Flags

How do we detect emerging psychosis?

What signs should raise concern?

What does good assessment look like?

Mrs. X had recently returned to work after being absent for a few months. At first, she was quiet in meetings. Then she began skipping them altogether.

When a colleague called, she whispered that the office phones were tapped. She said "they know everything I think."

She agreed to an assessment only after her partner noticed she hadn't eaten in two days and was afraid to leave the house.

Flags

Unusual suspiciousness, perceptual changes, or fixed odd beliefs

Sudden social withdrawal, functional decline, or flat affect

Disorganized speech, derailment, or illogical thoughts

Reports of "mind reading," "being watched," or "hearing things"

Family/friend concern without clear explanation

Best Practices

Start with a collaborative, stigma-free interview

Include direct but gentle questions about unusual beliefs and perceptions

Assess insight, reality testing, affect, and coherence of thought

Consider structured tools (e.g., BPRS, PANSS, CAPS, PDI, SAPS, SANS, etc.) in at-risk cases

Always ask about suicidality, substance use, and recent stressors

Precision Mental Health

Uses digital pre-screening to flag potential early psychosis risk

Incorporates AI-informed triage and structured intake interviews

Focus on fast access to care, including therapist-matching

Follows up on flags with specialized evaluation (telehealth or in-person)

Care pathways may include CBTp, medication consults, and family support

Summary: Assessment & Red Flags

Early signs often subtle — include withdrawal, odd beliefs, or perceptual shifts

Good assessment includes empathy, structured inquiry, and risk screening

Digital tools can augment human judgment and improve access

What are your challenges in working with people who experience psychosis? What has helped?

Communication Strategies

How to engage effectively

Mrs. X described a moment when her reflection no longer felt like her own.

She feared that something had taken over her body, and even her voice seemed unfamiliar.

The therapist’s calm response didn’t make the fear vanish — but it prevented things from escalating.

In that moment, what helped was not reassurance, but simply being seen without alarm.

Principles of Engagement

Principles of Engagement

Core Strategies

Establish Safety: Maintain a calm tone and open posture. Avoid sudden movements or challenges.

Validate the Experience: You don’t have to agree with the belief, but you can acknowledge the emotional impact.

Stay Curious: Ask open-ended questions to explore the meaning and context of the experience.

Limit Confrontation: Challenging delusional content directly may increase defensiveness or distress.

Respect Autonomy: Emphasize collaboration and choice wherever possible.

Digital Format

Digital Format

Digital Care Strategies

Start with rapport: In both messaging and video sessions, tone and empathy matter deeply. Use the person's name and reflect their language.

Assess stability early: Is the person grounded in reality? Are they experiencing perceptual distortions or paranoia?

Use simple, direct language: Avoid metaphors or abstract explanations in early phases. Clarity reduces uncertainty.

Offer structure: Provide predictable session formats, summaries, and check-ins to reduce fear and disorientation.

Document concerns: Clearly note flags like disorganized speech, flat affect, or delusional themes while maintaining trust.

Summary: Communicating in Psychosis

Effective communication is calm, validating, and non-confrontational.

Explore experiences gently without confirming or denying their reality.

Digital settings require even more attention to tone, structure, and safety cues.

Treatment Approaches

Evidence-based, person-centered, and sustainable care

Mrs. X was brought to urgent care by her sister after weeks of increasing isolation and disorganized behavior.

She believed her neighbors were sending her coded messages and hadn’t slept in days.

She received antipsychotic medication, but treatment didn’t stop there.

A coordinated team helped her rebuild routines, process trauma, and gradually reconnect with others.

Multimodal Care

Multimodal Care

Key Treatment Domains

Medication: Antipsychotics reduce acute symptoms. Careful titration and shared decisions matter for adherence.

Psychoeducation: Empowering patients and families with knowledge improves engagement and reduces stigma.

CBTp: Helps process distressing beliefs without invalidation. Evidence-based and effective in reducing relapse.

Family Work: Reduces expressed emotion, improves coping, and strengthens support networks.

Supported Employment & Housing: Restores identity and purpose — foundational to long-term recovery.

Recovery Framework

Recovery Framework

Recovery is More Than Symptom Control

Hope and empowerment: A belief in recovery and personal growth is central to treatment culture.

Shared decision-making: Patients define goals, preferences, and acceptable risks.

Integrated care: Address comorbidities, substance use, and unmet social needs holistically.

Digital tools: When used thoughtfully, apps and messaging platforms can support continuity, symptom tracking, and reminders.

After discharge, Mrs. X had trouble managing her appointments, prescriptions, and daily structure.

Her GP was unsure how to support her and hadn’t received the discharge summary.

A case manager reconnected the dots — coordinating care, checking in regularly, and involving her family doctor in the plan.

This continuity prevented relapse and supported her reintegration into daily life.

Transitions

Transitions

From Crisis to Community

Early planning: Begin discharge planning from day one, involving patient, family, and outpatient teams.

Bridging the gap: Provide follow-up appointments and low-threshold check-ins. Consider home visits or digital touchpoints.

Clear communication: GPs and social workers need timely, comprehensible discharge summaries.

Relapse prevention: Develop individualized crisis plans and involve the full support network.

Integrated Networks

Integrated Networks

Sustainable Multidisciplinary Care

Psychiatric support: Continue monitoring, med adjustments, and therapeutic engagement.

Primary care: Address comorbidities, monitor metabolic effects, and serve as accessible anchor point.

Case management: Ensure coordination, advocate for housing, benefits, and daily structure.

Peer support: Lived experience provides hope and authentic connection that complements clinical care.

Summary: Treating and Sustaining Recovery

Evidence-based care includes medication, therapy, family work, and psychosocial support.

Recovery is supported through continuity, collaboration, and person-centered planning.

Integration across services — psychiatry, primary care, digital tools — is key to long-term outcomes.

Real-world case studies and reflections

The Suspicious Neighbor: Emerging paranoia and early intervention

Voices on the Line: Acute psychosis during a crisis call

The Impostor Family: Delusional misidentification and trauma

The Silent Withdrawal: Subtle onset in a high-functioning individual

The Suspicious Neighbor

The Suspicious Neighbor

A., 21, recently moved into a student dorm. He started noticing whispers through the walls at night.

He believed the neighbor had installed listening devices and was trying to provoke him.

Though still attending university, he became preoccupied and distrustful. Early intervention helped prevent further deterioration.

Voices on the Line

Voices on the Line

L., 34, called a crisis hotline, reporting that government officials were broadcasting her thoughts via the radio.

She was terrified and disoriented, unable to distinguish internal thoughts from external voices.

This was her first psychotic break, precipitated by recent job loss, isolation, and sleep deprivation.

The Impostor Family

The Impostor Family

T., 28, became convinced that his parents had been replaced by identical impostors.

He described emotional disconnection and a strong sense of unreality at home.

A deeper trauma history surfaced later in therapy, suggesting that delusional misidentification masked unresolved emotional wounds.

The Silent Withdrawal

The Silent Withdrawal

F., 25, an accomplished student, began missing deadlines and isolating socially.

She stopped returning calls, often sitting silently for hours, lost in thought.

Only months later did she reveal she had been hearing voices criticizing her actions and doubting her own thoughts.

Thanks for your attention!